Rights by Rites

By Kate Watson

In The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager, Thomas Hine points to the various ways that different cultures throughout history signified their children had “come of age.” Boys in a few North American indigenous tribes left their families on “vision quests,” returning after an encounter with a guardian spirit who they believed would guard them for the rest of their lives. Girls in the Carrier tribe in what is now British Columbia would be shunned, ostracized, and totally secluded for three to four years after reaching puberty in a practice called “the burying alive.”

The Puritan families who came to the United States would send their teenagers out to apprentice with other families, effectively subcontracting the final years of parenthood to another set of parents. Once the Industrial Revolution was underway, it was popular in some areas for teenagers to leave their homes to work in factories, living in company-owned dormitories and squirreling away their earnings to send home.

These markers of adulthood may be hard to wrap our heads around as we look at our own adolescent children, cocooned as they may be in scattered PlayStation paraphernalia, half-empty bags of chips, and stinking socks. Prepared for a vision quest, the typical American teenager is not.

Earning a driver’s license, attending the prom, and graduating from high school were the closest thing to “rites of passage” that American teens post-WW2 ever had. But arguably more significant than all of these combined is the incredibly powerful device in their pockets—a machine they can use to book a flight anywhere they can pay for a ticket to go, learn anything they’re curious to know, and indulge in as many concurrent romantic relationships as they can match with on an app.

For this reason, we’d argue that the moment you decide to hand your child a fully enabled smartphone might be the moment their childhood, as you know it, comes to an end.

(No pressure.) That’s why we’re so passionate about helping you to choose to make the most of the process.

This article is meant to outline the steps to choosing exactly when to give your child a smartphone and how to give these moments the significance they should have. If you want to call it a modern-day rite of passage, we won’t stop you.

Step 1: Initiation

Giving your tween or teen a smartphone doesn’t have to feel like you’re in a dire situation—you’re choosing to do this, after all. The start of this process can, in fact, be a moment of pride.

At Axis, we recommend starting your child with one of the “dumb phones” (though we prefer the term “training phones”) currently available on the market. These phones don’t have browsers or an app store, and even their ability to send texts and make calls can be restricted. The idea is to give your child a phone like this in early middle school, when they are hopefully still young enough to be excited about that kind of device.

The “dumb phone” entry point provides a launching pad into conversations about responsible tech use, positive incentives, and managing screen time with a personal device. [See our “Five Conversations” article for more on those topics.]

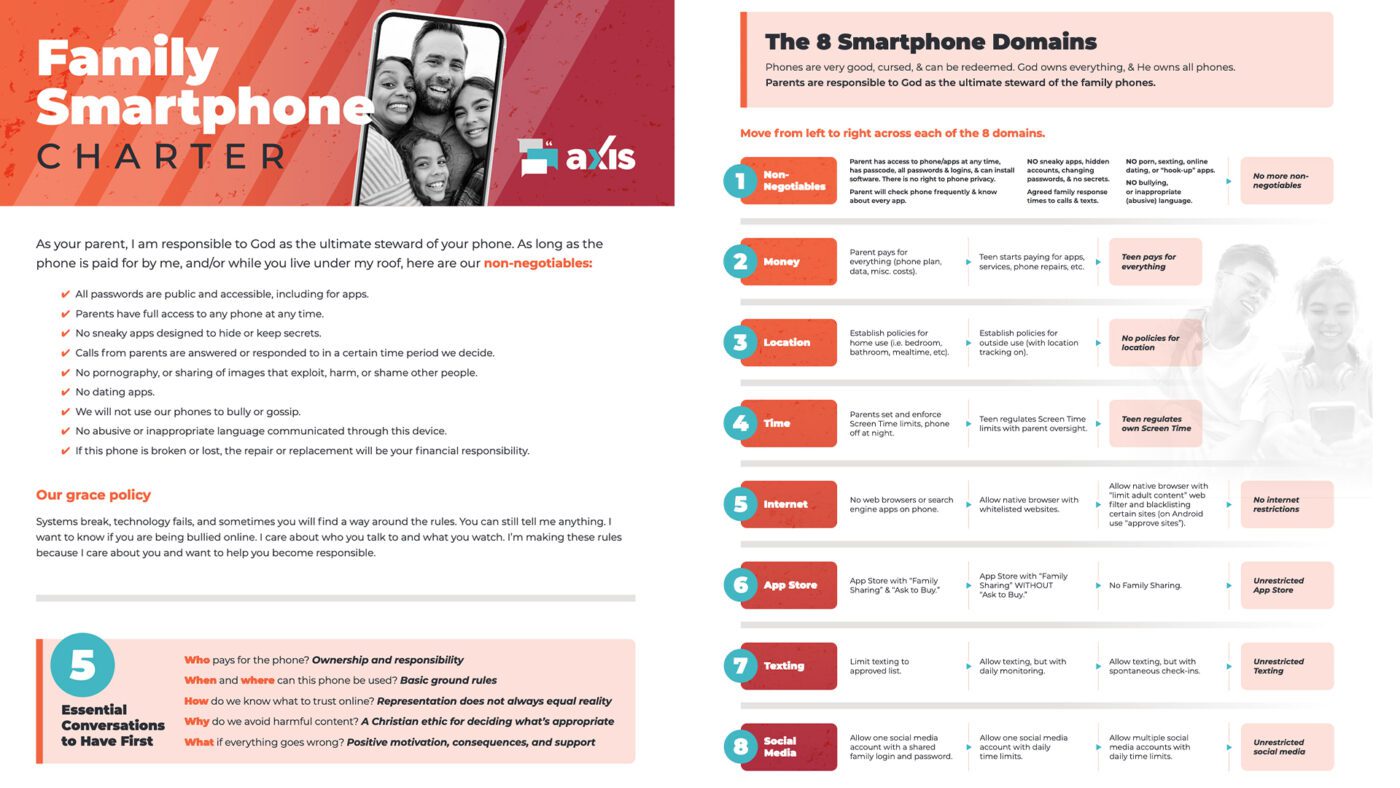

When you are gearing up to give your child a device that has more bells, whistles, and oh yeah, opportunities to fall into a gaping moral abyss, you should introduce the idea of the Smartphone Family Charter. This is a document that you can fill out in conversation with your teen, identifying your expectations as well as their hopes for what it might be like to have a phone of their own.

During this crucial time, we would also gently suggest modeling responsible phone use yourself as well as you possibly can. You’re about to ask a young person to do something really hard—something a lot of adults aren’t very good at. As Hine writes, parents often “want our teens to embody virtues we only rarely practice.”

If you’re considering giving a child a fully-enabled smartphone at this age but using parental controls, think carefully. You may be able to use parental controls to lock a twelve-year-old out of harmful content and encounters with predators—but there is a non-zero chance that a child in middle school can find other ways to access this sort of content. Make sure you go into this with your eyes wide open.

Some adults have expressed concerns that if children aren’t given access to a phone early enough, they won’t be able to “learn” how to use the technology properly, and maybe won’t learn how to practice self-control with technology either. But it’s a safe bet that they will have no trouble learning the technology, no matter when it is introduced. And research suggests that delaying phone access for people whose frontal cortex is not fully developed (i.e. teens) is probably a good idea. It could even be vital to helping teens form the neural connections they will need to act with self-control around anything or anyone in life, not just phones.

Step 2: Apprenticeship

Many families present a child’s first internet-enabled smartphone in a gift-wrapped box that’s meant to be a surprise, tucked under the Christmas tree or handed over on a milestone birthday.

It’s less exciting, and might feel even more intimidating, but we recommend telling your child exactly when they will get their first smartphone. Pick a date to hand the phone to them, and unless they violate the terms of their training phone, stick to that date.

And we mean “hand the phone to them,” not “hand them a shrink-wrapped box,” because you’ll want to open the phone and set the privacy restrictions the way you would like before your child has access to the device. Again, even if this solution isn’t bulletproof, we shouldn’t neglect to establish rules just because we think they might get broken.

You might be wondering how old your teen should be before you give your teen a (restricted, but still internet-enabled) smartphone. The truth is that every family is different, but introducing this around age 14 will allow you to track your child as they explore an ever-widening range of activities. It enables them to foster their fledgling network of personal connections, and to begin introducing social media apps should you choose to do so (see this link for a list of apps and the parental controls available on each app).

But because this is in the “apprenticeship” process, you should still have full access to your child’s phone and passwords. The message should be clear that the phone exists in your space and under your rules. As your teen reaches certain trust markers, you can gradually disable some of the more limiting restrictions so that the device becomes more functional.

Step 3: Closing Ceremony

Your teen is working with you towards an endpoint in this process. That endpoint is a fully-enabled smartphone that is fully theirs to steward. You might not be able to predict when that endpoint will come, but you should do your best to communicate with your teen as that date approaches.

Consider having a “closing ceremony” of sorts where your child’s phone “grows up” and the remaining apprentice-level restrictions are removed.

At this point, it’s not that your teen won’t have any rules on their phone. It’s more true to say that they will abide by the same rules you set for yourself. This would hopefully still imply limits on where the phone is charged at night (in a public area, out of the bedroom) as well as what types of apps are allowed.

Hine writes, “The weaknesses we see in youth are our own, and we know it.”

If you want your teen to still have an accountability app of some sort installed, install it on your phone, too and give them your passwords. This signifies a level of respect and acknowledgement that sometimes, even adults need help being held to account.

Moments on this journey toward having a phone with all of its functions might feel serious, and there may have been tension. This “ribbon-cutting” moment, when your teen is allowed to become a full member of the smartphone-carrying community, should feel celebratory and sweet.

Leading child psychologists and ethicists suggest that giving a teen a smartphone with social media access at 16 might be the “sweet spot” to shoot for. Of course, your teen might think you’re impossibly old-fashioned if you make them wait this long for a “graduated” phone. (Even though, in truth, you’re on the cutting edge of academic research, the medical literature, and proposed legislation.) But every parent has to make the decision they think is best for their kids.

Final Thoughts

Rituals may seem like anachronisms from another time, but we suspect they hold a power we cannot quite comprehend. The ritual Jesus gave us to remember Him has survived in the Christian tradition for over 2,000 years.

Parents who are raising Gen Z and Gen Alpha have seen plenty of parental panics come and go. The satanic panic, hand-wringing over MTV, and book bans have seized the minds of parents throughout the last several decades. It is debatable whether the rhetoric or rage over these relics contributed positively to anyone’s spiritual formation. Falling church attendance rates and a growing body of religious “nones” would imply quite the opposite.

If we reframe the way we understand “teenagers” and think of these individuals as adults in training—as people who are working through a winding maturation process that is outside of their control, governed by their surrounding culture and their own rapidly shifting biology—our empathy for their experience deepens.

We become more willing to relinquish some level of our control, and we look for opportunities to cultivate adventure and formally recognize moments of triumph. We can promise that adulthood is something to cherish, to earn, and to celebrate—and that the endpoint of childhood might be bittersweet, but it does not have to be sour.

“Being a teenager is not an identity, but a predicament most people live through,” Hine writes. A predicament that involves learning self-control, making mistakes in front of people you admire, and longing to prove yourself trustworthy. By ritualizing the smartphone onboarding process, we can redeem the way we think about our teens. Maybe in some ways, we can even redeem the little black mirrors we keep in our pockets, too.

Kate Watson is a writer, editor, and mother of three living in New York’s Hudson Valley. She writes about culture, community, and parenthood for outlets like Christianity Today, Relevant, Insider, and Vox. Kate is the managing editor at Axis.