Feel discouraged?

“Really this is more about me and the glitches in my own brain. I think most people can handle it. But for whatever reason, I don’t seem to have the self- control for a full-fledged modern smartphone.” — Jake Knapp, author and time management strategist

Gosh, don’t most of us feel this way? We have so many ways that we want to spend our minutes. With an extra hour a day, we would love to learn a language, garden, take a stroll with our loved ones, or finally read a good book. Yet in the face of empty space (or Monday’s doldrums…hello mountain of laundry and pile of soggy dishes), what do we turn to? For many of us, it’s not what actually feels important, meaningful, or life-giving. Instead, it’s usually our phones—catching up on email, checking the weather, scrolling through our social media app of choice….

Feel guilty and powerless? Talking about smartphone addiction can be disheartening, partially because it means listening to information that we’re mostly sick of hearing. Yeah, yeah, yeah…we should put down our phones to engage with the real world. And yes, we know that teens are growing up in a frightening world of rapidly evolving technology that we can’t keep up with. Our kids are experiencing more anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation than we ever did, and all this is strongly correlated with tech use. Cue more guilt. Because a lot of the time, we can’t even control our own smartphone use.

It seems pretty clear that information alone isn’t helping us change our habits. We keep turning to our phones when we don’t want to. We spend more time on them than we’d like.

Rather than completely re-hashing the problem of smartphone addiction, this Parent Guide provides self-reflection questions scattered throughout and a few practices to try. Some exercises are just for you (because asking your teen to change their smartphone habits means being willing to evaluate your own phone use first), and some practices are for your teen. We’ll let you know which are which. Some may work for you and your teen. Some may fail epically. In any case, we hope you walk away with a better understanding of what you expect your smartphone to give you, why you look at it when you do, and what smartphone habits you want to model for the teens in your life.

So let’s begin with a self-reflection question. If it’s helpful, find a notebook and pen to jot down a few of your initial thoughts: What is your smartphone for?

Related: Should Kids & Teens Have Cell Phones? Pros & Cons

What is it for?

Neil Postman wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death in the 1980s when hefty living room squares, not portable pocket rectangles, caused most of the angst around wasted time and harmful technology. Postman poses this question to frame any discussion of technology: What is it for?

Phones, like all tools, have telos, a Greek word that means “purpose” or “objective.” Here’s an example: Hiking boots protect our feet over miles and miles of rough terrain, helping us get from one place to another safely. High heels aren’t all that comfortable, but they complete an outfit or provide an air of professionalism. Hike in high heels, you’ll sprain an ankle. Show up to an interview in Chacos, you’ll raise some eyebrows. It’s not because the shoes are dysfunctional or bad, it’s because they’re being used for the wrong purpose. And this goes for so many of our tools.

Knowing what we expect from a tool—what function we need it to serve and what outcome we want it to produce—is the first step in figuring out how to use that tool. So what are we expecting from our phones? And do those expectations match our phones’ design? Can our phones give us what we want?

Pause and reflect: When have you felt disappointed by your phone use? When have you felt satisfied? What made the difference?

Are smartphones really addictive?

The term “addiction” is usually associated with substances like drugs and alcohol. But addiction can describe compulsive behaviors as well:

The compulsion to continually engage in an activity or behavior despite the negative impact on the person’s ability to remain mentally and/or physically healthy…defines behavioral addiction. The person may find the behavior rewarding psychologically or get a “high” while engaged in the activity but may later feel guilt, remorse, or even overwhelmed by the consequences of that continued choice.

The more we learn about our brains, the more we realize how nuanced addiction is. Researchers used to believe that certain substances (think meth) are so powerfully addictive on their own that anyone who took them consistently would be hooked, no matter who they are or what their environment is like. But this isn’t the case.

Researchers started wondering why elderly patients were able to use hardcore narcotics to manage pain after surgery without becoming addicts. Cue the famous rat studies. In phase one, rats were placed in cages with two water bottles, one with plain water and the other with meth-laced water. As expected, the rats loved the meth- water and died quickly. But one key factor was overlooked for a long time. The rats were alone with nothing meaningful or interesting to do. That’s when a researcher decided to create “Rat Paradise” with toys and other rat friends and whatever else rats dream of. In Rat Paradise, the rats didn’t drink the meth-infused water. They didn’t need more dopamine because they were already quite content. Interesting, right?

For us, this sense of contentment (or not) is generally determined by what Johann Hari calls humanity’s innate needs, things we need for a sense of fulfillment:

- Autonomy – the ability to make choices that matter.

- Intimacy – feeling seen and known.

- Belonging – feeling wanted.

- Mastery – the ability to develop meaningful skills.

There are tons of wonderful ways to meet these needs. Unfortunately, there are lots of destructive ways to try to meet them that feel good in the moment but backfire later.

When we check our smartphones 10 times in two minutes, what are we looking for? When we scroll through Instagram for an hour, even though we told ourselves we wouldn’t do that again, what are we hoping to find?

The rat studies show that addiction is a signal about our unmet needs. It indicates that something is amiss. So instead of focusing on the addictive process or substance (drugs or the smartphone), we should look deeper into our pain and ask some questions:

- Why am I feeling this way?

- What is missing in my life?

- What am I not handling well?

Meth addicts are rarely under the illusion that drugs are healthy. Users know that their addiction is destroying them. In the same way, most of us are aware that smartphones not only won’t, but can’t give us what we’re looking for. Some of us are trying to meet legitimate, basic needs with something that was never designed to fulfill us. An adage from the 12-Step Program notes, “You can never get enough of something that’s not quite enough.”

Most of us aren’t actually addicted to our phones in the truest sense of the word “addiction.” If we went without our phones for 24+ hours we might feel uneasy or like we’re missing something, but we wouldn’t experience withdrawal symptoms like shaking or having a panic attack. So a better phrase for “smartphone addiction” is probably “smartphone overuse.”

What researchers do agree on is the fact that adolescents are more likely to demonstrate addiction-like symptoms with their cell phone use than other age groups. Studies show that cell phone use peaks during the teen years and gradually declines thereafter. Excessive cell phone use among teens is so common that 33 percent of 13-year-olds never turn off their phone, day or night. And the younger a teen acquires a phone, the more likely they are to develop problematic use patterns.

Either way, we can develop a healthier relationship with our pocket rectangles, whether this involves overcoming literal, clinical addiction, or developing healthier rhythms when we feel like our phones are encroaching on things that really matter.

Our teens desire the things that are deep, true, and real; smartphone overuse can hijack those desires. Like all of us, our teens want to look back at their lives with fondness, excitement, and gratitude. They ache for community—for the kinds of friendships that swim the full length of the pool…laughing uproariously at a stupid meme one minute and then seamlessly moving to the deep end to talk about a song that made them cry the other day, or their fear of not finding a job in a world that’s falling apart.

These deepest and truest and best human connections are hard to cultivate. They take time. And we’re impatient. So we use technology as a shortcut for quick hits of dopamine and serotonin (the brain’s pleasure chemicals). This is why smartphone design is so influential.

Are smartphones designed to be addictive?

Silicon Valley, where our phones and apps are designed, is full of app developers

who know how the brain works, and who design technology to keep us hooked. Ex- Facebook President Sean Parker put it like this: “It’s a social validation feedback loop… exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.”

We live in an attention economy. Marketers know that if they can get the right people’s attention, they can make more money. The more time we spend on our phones, the more ads we see, and the more marketers know about us (she looked at that photo for five seconds, he watched 83% of that video). This allows for targeted ads that are more effective at selling us the products we’re interested in. Scary, right? This is why social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram…) are free, because our attention is the product. These creators have robust financial incentives to keep us using their apps for as long as possible.

As depressing as all this can sound, we’re actually kind of encouraged to know that even the most disciplined people struggle to use their phones well.

App design + brain chemistry = hours of scrolling, and that can happen to anyone. If you’re interested in the specifics of addictive app design, you’ll be fascinated by these features (Silicon Valley’s “Playbook of Persuasive Techniques”):

Variable schedule rewards: Like a slot machine, we pull down on social media apps to refresh. Sometimes we get a reward (new content) and sometimes we don’t. This randomization keeps us hooked because we never know what to expect.

Infinite scroll: We could scroll through Facebook forever…scroll just a little further, and what mini hit of dopamine could be waiting?

Notification bursts: Sometimes we check our phones to find nothing. And then there are the times that everyone in the world seems to have liked our post. These randomized notifications keep us guessing, make us feel wanted, and trigger a strong desire to check the app to see what’s happening.

Social approval: Likes, comments, and followers feel desperately important because we innately care what others think of us.

Try this: If you have a Netflix subscription, watch The Social Dilemma as a family. Then discuss these questions:

- What was surprising to you?

- Did you disagree with anything?

- What resonated?

- Do you want to change any technology habits as a family based on what you learned?

Why do teens spend so much time on their phones?

Every tool we use promises us something. Run faster with Nike shoes and take on the identity of a strong, disciplined athlete. Stay focused with Starbucks coffee and identify as a productive, capable person.

Look around and find a product (or anything you spent money on): What does it promise? Now think about your phone (or more specifically, your teen’s phone)…what does it promise your teen?

Here are a few things your teen’s phone might be promising them:

- Freedom

- Comfort

- Entertainment

- Community

- Autonomy

- Self-exploration & expression

- Escape

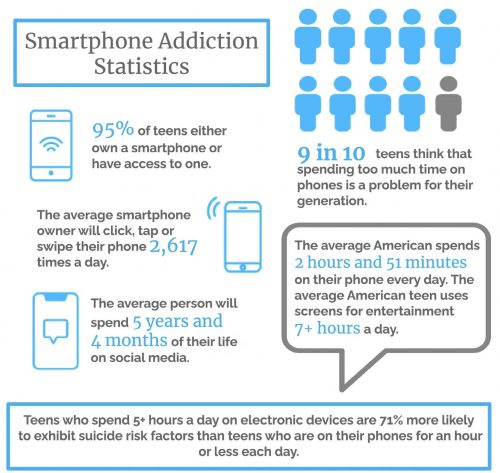

These promises and motivations help explain the (dreaded) smartphone usage statistics:

These statistics are startling, but when we dig beneath the surface to the reasons that we’re looking at our phones, we often find deeper issues to address. Spending less time on our phones won’t solve the root issue of an inability to tolerate boredom or the pain of a divorce that we don’t want to think about. Teens probably need more than screentime limits, because phone overuse is often an indication of deeper problems.

How can we help teens become addiction resistant?

1. Encourage self-evaluation.

Help your teen figure out what they use their phone for, and then evaluate whether their habits are matching the telos of their phone. Ask lots of questions and try not to talk too much. Encourage them to come to their own conclusions. Here are a few questions to start with:

- What do you love about your phone?

- What do you dislike about your phone?

- What is your phone’s purpose?

- How much time do you think is healthy to spend on our phones each day?

2. Practice emotional intelligence.

These should be our guiding questions when engaging with media generally, and smartphones specifically:

- What do I need?

- What do I want?

- What am I looking for?

Help your teen develop the ability to understand why they are turning to their phone and to figure out what they are looking for; to notice their emotional state whenever they’re on Instagram, and to ask what that emotion is telling them.

Try this: For 1–3 days, every time you unlock your phone name one emotion that you’re feeling. If it’s hard to figure out how you feel, use this emotion wheel. Do you notice any patterns? Are there certain emotional states that drive you to look at your phone more often? How do you feel after you’ve been on your phone?

3. Embrace boredom.

Unstructured time is where creativity happens (read our Parent’s Guide to Boredom if you want to learn more). This is time with nothing to do (counterintuitive in our productivity-driven culture!). Create tech-free zones so that you and your teen have space to process the continuous inputs that come at you all day long (music, books, podcasts, etc.). This can look like a long walk, time just sitting around, driving with the radio off….

4. Embrace limitation.

Phones, and especially social media, promise omnipresence, that we can be in multiple places at once. But to be human is to be limited. We are always missing out on something. And in a way, this is true freedom. Embracing the present moment fully, because that’s all we actually have.

5. Find something better.

As Dr. Jordan Peterson said, “Esteemable people do esteemable things.” If an alcoholic is trying to defeat alcoholism, they have to find something more inspiring and captivating and beautiful to them than alcohol. This

is true for any goal we set as we try to overcome bad habits. Adventure is a better motivator than prohibition. Romance, edginess, something that stretches and challenges us…these are the things that compel us to risk everything in pursuit of

a meaningful life. So encourage your teen to think about all the ways they want to spend their time (learning computer programming, being with people they love, etc.) and then figure out where time on their phone fits into an intentional life.

6. Develop a nurturing environment.

Remember that addiction involves a quest, an attempt to fill an ache or forget a hurt. If your teen is turning to their phone to meet an innate need (belonging, intimacy, mastery, or autonomy) you can help them to find other outlets. Maybe sit down together and brainstorm different ways to meet each of those needs. As Johann Hari notes, “The opposite of addiction is not sobriety. The opposite of addiction is connection.”

7. Allow for failure.

Thankfully, God set the world up in a way that keeps us searching for real things. Trial and error, in small, safe doses, is actually how many of us learn! So let your teen figure out that hours of Instagram honestly isn’t that great. Especially if they are older, let them spend too much time on their phone and figure out for themselves that it can’t satisfy their deepest cravings. We wish there was a formula to do this perfectly, but instead of pretending that the same strategy will work for every kid, we’ll just pray alongside you for tons of discernment and direction from the Holy Spirit, helping you know when to say something about your teen’s tech habits, and when to silently let them learn their own lessons.

8. Future Authoring exercise.

The following exercise will require some time. You and your teen might be able to answer all of the questions in one sitting, but it might also be a good idea to discuss your answers at the dinner table over the span of a few weeks. It’s an exercise that Jordan Peterson recommends called Future Authoring, and is best suited for mature teens (probably high school age).

Essentially, you as a parent, mentor, or leader are trying to inspire your teen toward not just good phone habits, but toward a holistically good life. You’re helping your teen identify what they want to stand and live for, and then evaluating whether or not their habits are taking them toward their values. This isn’t judgmental or legalistic. You won’t condemn any of their processing. Instead, you’re helping them cast their own vision, helping them to reach their own conclusions instead of just imposing boundaries.

We’ve tweaked the exercise a bit to include time to listen for God’s voice as you and your teen answer the questions.

Read this together: Jesus was great at asking questions. There’s a story in Mark where Jesus is about to heal a blind man, but instead of just giving him sight, Jesus asks him, “What do you want me to do for you?” In a way, Jesus asks each of us this question…what do you want? What are your deepest longings, what does your heart ache for? Now, of course, Jesus isn’t a genie in a bottle, existing to make our lives fun. The best life isn’t always the wealthiest or most successful. But Jesus’ fulfillment is real, and actually deeper than the surface level things we often want. He said, “I came to bring you life, and life to the full.”

9. Imagine your life 3-6 months from now.

What would abundance look like? What would you want Jesus to do for you? Take a few minutes and actually write down your answers to these questions. If you want, write them as a prayer. Hold your dreams and longings in God’s presence and see what the Father has to say about them:

- What would your relationships be like if they could be the way you want them to be (with family, friends, your significant other)?

- What would you have if you could have what you wanted?

- What kinds of things have you experienced over the last few months?

- How will you be conducting yourself in your job or your school life?

- What will you be learning (a language, mountaineering, an instrument, computer programming, yoga, candle-making…)?

- What part does your phone play in your life? How much time are you spending on your phone each day?

10. Freak yourself out.

Now that you’ve imagined the kind of person that you want to be, take stock of your idiosyncrasies and weaknesses and imagine yourself at your worst, with every bad habit continuing.

- Where would you be in 3-6 months if this was the case?

- What kind of hell would you realistically create for yourself if you let your worst run wild.

- What are you afraid of if you stay at your worst?

- What do your habits with your phone look like in this scenario?

As James Clear points out, even the tiniest habits compound over time…The little decisions we make each day determine where we end up, just like the nose of a plane pointing the wrong direction by just a few feet can land you in D.C. instead of New York City if you take off from LA. So encourage your teen to think about where they want to land. What type of person do they want to be? And then reflect on whether their technology habits are derailing them or moving them forward.

These kinds of self-inventories can easily lead to a lot of self-directed guilt (gosh, I’m

a trash person and consistently fail to live in line with my values), discouragement,

or legalism (I’ll get my life together through pure willpower). That isn’t our goal. God sees us as we are and accepts us, flaws included. He also wants to enable us to live like Jesus lived, bearing His image in a beautiful and deeply fulfilling way. This doesn’t have to be larger than life or “radical.” It could start with buying your teen (and yourself) an alarm clock so that you’re not looking at your phone first thing in the morning. Little boundaries, little limitations, and little decisions all matter. Even just asking the Holy Spirit, “How do you want me to use or not use my phone for the next hour?” is an exciting starting place. What would happen if we purposefully invited God’s input about not only our values but the apps we download or don’t download? What would change? What could happen?

Final thoughts

Digital discipleship is the brave new world of parenting. Your teens are the first generation to grow up as digital natives in a digital world, and you are part of the first generation of parents to help them navigate the unknown. Parents before you haven’t faced this challenge. So take a deep breath. This is new territory. And you’re going to make mistakes. Your kids will be okay; every parent makes mistakes. You have the privilege of walking with your teen toward health and growth, helping them steward their attention wisely, and discovering how to love God and others in a world of smartphones.

Apps we love

The Center for Humane Technology partnered with Moment to rank apps based on users’ reported well-being after use. Here’s their list of apps, ranked from Most Happy to Most Unhappy, and accounting for how time spent on the app impacts happiness. Here are a few other apps we enjoy:

● Moment

● Common Prayer

● Pray as you go

● Reimagining the Examen

● Pause

● Libby

● Chess

● Pomodoro

● Down Dog

● AllTrails

● Duolingo

● Productive

● EveryDollar

● rTribe

Try this!

Digital Sabbath. Pastor John Mark Comer recommends these boundaries around technology:

- Once a week take an evening off from devices. Put your phone to bed before dinner and don’t use it again until the next morning.

- Once a month take a full day away from devices. 24 hours intentionally tech-free to make time for other things.

- Once a year plan one tech-free week (a vacation or time at home).

Look through The Center for Humane Technology’s recommendations for parents and educators. They include:

- Going Grayscale

- Turning off notifications

- Digital Well-Being Guidelines

Consider The Light Phone!

Mindfulness Practices:

- Go for a “senses walk.” Engage all five senses as you walk around your neighborhood or a park. What five things do you see? What four sounds do you hear? What three sensations do you feel? What two aromas do you smell? What do you taste?

- Do a body scan. Starting at the top of your head and working down all the way to your toes, slowly notice how your body is feeling. Is your throat constricted? Are your shoulders tense? Are you breathing deeply or shallowly? Where are you relaxed? Do you have any pain? Once you’ve observed the state of your physical body, slowly and intentionally relax (it helps to either lay down or sit comfortably with your feet planted). Unwrinkle your forehead. Remove your tongue from the roof of your mouth and unclench your teeth. Relax your shoulders. Let your feet flop out to the side if you’re lying down. Engage in this practice of stillness for 30 seconds to five minutes. How do you feel?